About a month ago, I posted that the Diagnostic Center for Population and Animal Health (DCPAH) at Michigan State University had announced that the reagents for their parathyroid hormone related protein assay (PTHrP) were not longer available.

This week Michigan State University's DCPAH announced that they are back in business and can again run serum samples for both parathyroid hormone (PTH) as well as PTHrp.

This is the only laboratory that offers the PTHrp test used in the workup for dogs and cats with hypercalcemia. So this is great news that this important assay is up and running again soon.

See the Announcement page on the DCPAH website for more information.

Źródło: endocrinevet.blogspot.com

Due to an inventory error, we have found ourselves with 3 bottles of synthetic ACTH (Cortrosyn) that have an expiration date of a month from now. Would you recommend reconstituting all 3 vials and freezing into aliquots at this point? Before I throw out several hundred dollars worth of Cortrosyn, I wanted to ask you opinion.

Additionally, for future use, what is the current dosing recommendation when using previously reconstituted Cortrosyn? Are there special considerations for freezing it?

Thanks so much for your help.

My Response:

Officially, I cannot condone the use of drugs past their expiration date, but it makes some sense to me that if you reconstitute it and freeze it now, that you could keep the aliquots for 6 months. The problem is if you get results that you weren't expecting (ie, lower than expected ACTH-stimulated cortisol values), then you have to question whether the Cortrosyn is still potent, but I'd suspect it will be okay.

If it was still in date, you could try selling some to neighboring clinics, but I'm not so sure you can or should do that with expired drug.

Click here to see my previous post about how I recommend reconstituting and freezing Cortosyn for future use. And click here to see my post on the best dose to use for ACTH stimulation testing.

Źródło: endocrinevet.blogspot.com

'm treating a 10-year old, F/S Bichon Frise who has been on 2.5 mg of prednisone daily for months. Her appetite has always been good, but recently she has become extremely ravenous on the same dose of prednisone. In addition, lately she has become noticeably more polyuric and polydipsic (PU/PD).

So, I suspect that naturally-occurring Cushing's syndrome may be developing — oddly, while taking predisone. We found not abnormalities on her routine lab work except an very high serum alkaline phosphatase activity of 1100 U/L (reference range < 100 U/L).

My thought is that stopping the predisone for a few days should be enough to allow for us to perform an ACTH stimulation test or a low-dose dexamethasone suppression test (LDDST). That amount of time will allow the predisone to leave the system so there won't be any interference with the testing. It would seem to me that an interval longer than a few days shouldn't be needed.

That being said, everyone keeps telling me it will take a few months for the adrenals to regenerate once I stop the prednisone. Presuming this dog has truly developed PDH or an FAT, does it make any sense to you that I should have to wait any longer than just a few day to let the prednisone out of the body?

My Response:

Good question. If this dog's pituitary and adrenal glands are "normal" (ie, she does not have naturally occurring Cushing's disease - either pituitary-dependent hyperadrenocorticism or a functional adrenal tumor), then the prednisone could feedback on the dog's normal pituitary gland to inhibit ACTH secretion. With time, the resulting low circulating ACTH concentrations would lead to atrophy of the inner 2 zones of the adrenal gland that secrete cortisol.

If you stop the prednisone for 24-48 hours and do an ACTH stimulation test in that dog, the results would likely show a low to low-normal basal cortisol with a "blunted" cortisol response to ACTH stimulation (generally > 2.0 ug/dl but < 6 ug//dl). Despite the suppression basal and ACTH-stimulated cortisol values, that same dog with iatrogenic hypoadrenocorticism could show clinical signs of iatrogenic hyperadrenocorticism (due to the direct glucocorticoid effects of the prednisone).

Now, if this dog really does have natural Cushing's syndrome (either pituitary-dependent hyperadrenocorticism or adrenal tumor), the doses of prednisone you are giving will NOT be high enough to shut off pituitary ACTH secretion or suppress adrenal cortisol section. (This "resistance" to glucocorticoid negative feedback in Cushing's disease is the whole physiologic basis for use of the low-dose dexamethasone suppression test.).

So in this dog with Cushing's syndrome, performing an ACTH stimulation test after being off the prednisone for 24-48 hours would show a normal to high basal cortisol with a high-normal to exaggerated serum cortisol response. In other words, the prednisone would not affect the ACTH stimulation test because the adrenal cortex would still be hypertrophied.

Another important point: in this scenario, you want to use and ACTH stimulation test, not the low-dose suppression test. If another long discussion for me to explain the reason why that's the case, but you can get false-positive results in dogs with iatrogenic Cushing's disease so you do NOT want to use a low-dose dexamethasone suppression test in this dog, at least as your initial test.

Źródło: endocrinevet.blogspot.com

Buster is overweight at 17 pounds, but he has lost 3 pounds on a weight loss plan. Other than being overweight and increased bronchovesicular sounds on auscultation, his physical examination was unremarkable, with great skin and haircoat.

His overall blood work was totally normal, with the exception of a low serum T4 concentration (0.4 µg/dl; reference range = 0.8-4.0 µg/dl). I added on a free T4 value, expecting it to be normal; however, it was also low at 5 pmol/L (reference range = 10-50 pmol/L).

My question is this: Can the euthyroid sick syndrome can suppress serum T4 and T3 levels in cats, as drugs or disease can do in dogs? I do not feel treatment with levothyroxine (L-T4) is warranted in this cat, but I don't want to ignore low thyroid values either unless I can explain why they might be low.

I'd greatly appreciate your insight on this curious case.

My Response:

I agree with you that Buster would not likely benefit from L-T4 supplementation.

Hypothyroidism is a clinical diagnosis -- if there aren't any clinical signs, the finding of low serum thyroid hormones values alone doesn't justify treatment. This is even more true in cat, where spontaneous hypothyroidism has only been documented in only a couple adults cats. Congenital hypothyroidism in kittens is much more common, but Buster certainly doesn't have congenital hypothyroidism since he is 10 years old!

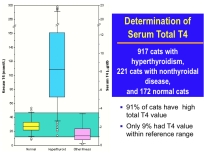

Figure 1: Notice that the total T4 concentrations are low in about half of the cats with nonthyroidal disease (pink box plot on right).

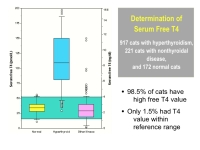

Figure 2: Notice that the free T4 concentrations tend to stay within normal range in cats with nonthyroidal illness (pink box plot on right), but values are subnormal in about 20% of these cats. Also note the falsely "high" values in other sick cats, illustrating some of the problems with the free T4 assay in cats.

It certainly is possible that his asthma and steroid therapy has suppressed both his total and free T4 concentrations. In 2001, I wrote a research paper (1) where we measured total and free T4 in cat with hyperthyroidism and nonthyroridal illness. As you can see in Figures 1 and 2, both total and free T4 were suppressed to low levels in some of the cats who were ill.

Reference:

1. Peterson ME, Melian C, Nichols R. Measurement of serum concentrations of free thyroxine, total thyroxine, and total triiodothyronine in cats with hyperthyroidism and cats with nonthyroidal disease. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2001;218:529-36.

Źródło: endocrinevet.blogspot.com

The dog or cat does not have to be fasted overnight, and lipemia does not appear to “clinically’ affect serum cortisol values. However, having a nonlipemic sample may be better in some situations, especially if serum cholesterol or triglycerides are being measuring on same sample.

Remember that the ACTH stimulation test is the most useful test for monitoring dogs being treated with trilostane (Vetoryl) or mitotane (Lysodren) see my blog entitled, Diagnosing Cushing's disease: Should the ACTH stimulation test ever be used? Both medications are fat-soluble drugs and must be given at time of meals, or the drugs will not be well absorbed.

With trilostane, it’s extremely important to give the morning medication with food, and then start the ACTH stimulation test 3 to 4 hours later.

Fasting these dogs on the morning in which the ACTH stimulation test is scheduled should be avoided since it invalidates the test results.

When a dog ‘s food is withheld, the absorption of trilostane from the gastrointestinal tract is decreased. This leads to low circulating levels of trilostane, resulting in little to no inhibition of adrenocortical synthesis. Therefore, serum cortisol values will higher when the drug is given in a fasted state than when it is given with food.

The higher basal or ACTH-stimulated cortisol results could prompt one to unnecessarily increase the daily trilostane dose. That misjudgment may lead to drug overdosage, with the sequelae of hypoadrenocorticism and adrenal necrosis in some dogs.

Recommended ACTH stimulation test protocol:

There are many different published protocols for how to perform the ACTH stimulation testing. Both ACTH gel or synthetic ACTH can be used, but over the last 2 decades, the use of cosyntropin (Cortrosyn) has become the “gold standard” preparation for ACTH stimulation testing.

There are many different published protocols for how to perform the ACTH stimulation testing. Both ACTH gel or synthetic ACTH can be used, but over the last 2 decades, the use of cosyntropin (Cortrosyn) has become the “gold standard” preparation for ACTH stimulation testing.In the USA, Cortrosyn is available through Henry Schein (800-872-4346; www.henryschein.com) where it can be purchased as an individual vial ($68/vial) or a box of 10 ($720 per box or 68/vial).

This is the protocol for the Cosyntropin (Cortrosyn) ACTH stimulation test that I recommend:

1. Collect baseline serum or plasma sample for cortisol determination.

Use of a serum separator tube should be acceptable for serum cortisol measurements, but check with your laboratory to ensure proper sample collection.

2. Prepare the ACTH preparation for administration (see below).

Cortrosyn is supplied by the manufacturer as a lyophilized cosyntropin powder in vials containing 0.25 mg (250 µg) of ACTH to be reconstituted with sterile saline solution.

In order to make this test more cost effective when using Cortrosyn and to make it easier to administer this dose to smaller dogs, I recommend diluting the Cortrosyn and dividing the solution into 25-µg to 50-µg aliquots in a tuberculin or insulin syringe, and then refrigerating or freezing the capped syringe.

For specific guideline on how to dilute the Cortrosyn and store it to extend it’s shelf-life, look for may next post entitled: How to extend your supply of Cortrosyn and lower the cost of ACTH stimulation testing.

3. Administer the cosyntropin at a dosage of a 5.0 µg/kg, up to a maximum dose of 250 µg; 1 entire vial).

This 5.0 µg/kg dosage will result in maximum stimulation of the adrenocortical reserve, the most important criteria for any ACTH stimulation protocol.

4. In dogs, the Cortrosyn can be administered either IV or IM, with equivalent cortisol results. Obviously, if the dog is dehydrated or in shock, the Cortrosyn must be administered intravenously.

In cats, its best to administer the Cortrosyn IV, because the adrenocortical response is more consistent and the peak is higher. Given subcutaneously, the Cortrosyn is not well absorbed in cats. In addition, giving Cortrosyn by the IM route is painful for cats and should be avoided.

5. Collect post-ACTH serum sample for cortisol determination 1 hour later.

6. After the clot has retracted, centrifuge both samples.

If using plasma or a serum tube without a separator, aspirate the plasma or serum and transfer into a plastic or glass vial.

Test protocol for tetracosactide (Synacthen):

If you live in a part of the World other than the USA, it’s likely that you will be using tetracosactide (Synacthen) rather than Cortrosyn as the synthetic ACTH preparation. The chemical structure of tetracosactide and cosyntropin are identical, and the test protocol outlined above will work. However, because the cost of Synacthen is much less than Cortrosyn, it is common practice to administer Synacthen at the dose of a half vial (125 µg) to a cat or small dog and an entire vial (250 µg) to a larger dog, rather use the 5-ug/kg dosage.

If you live in a part of the World other than the USA, it’s likely that you will be using tetracosactide (Synacthen) rather than Cortrosyn as the synthetic ACTH preparation. The chemical structure of tetracosactide and cosyntropin are identical, and the test protocol outlined above will work. However, because the cost of Synacthen is much less than Cortrosyn, it is common practice to administer Synacthen at the dose of a half vial (125 µg) to a cat or small dog and an entire vial (250 µg) to a larger dog, rather use the 5-ug/kg dosage.Źródło: endocrinevet.blogspot.com

Bailey is a 14-year-old male neutered domestic short hair who was diagnosed with hyperthyroidism by another veterinarian about 3 years ago and has been on methimazole since then. He also has a history of chronic constipation that has been well controlled in the last year on enulose (Lactulose) only.

I last saw Bailey a year ago, at which point he was doing well clinically but had lost about 1 lb. since his last check. At that time, he was on 5 mg of methimazole BID. A geriatric profile at that time showed a total T4 of 3.3 µg/dl, a normal CBC and serum chemistry profile (creatinine = 1.5 mg/dl, BUN = 23 mg/dl), and a urine specific gravity of 1.065. I recommended increasing his dose of methimazole to 7.5 mg in the morning and 5 mg in the evening and rechecking in 4-6 weeks.

The owner did increase the daily methimazole dose but did not follow up with us until now. Bailey has lost an additional 3 lbs since July and has developed polyphagia, polyuria and polydipsia over the last month. On exam yesterday, my main physical exam finding was that he now has a fairly large mass in his left ventral neck area (about 3-4 cm, slightly firm and irregular), which I had not noted on the last exam. His blood work from yesterday showed a T4 of 1.9 µg/dl, and very normal renal function (serum creatinine = 1.1 mg/dl; BUN = 22 mg/dl, USG =1.030).

So, I'm suspicious that the thyroid mass is or has become a carcinoma at this point. But would you expect the cat to lose weight secondary to a thyroid carcinoma even if the T4 is within normal range? Could it be secreting another hormone to cause the weight loss?

I thought I should recommend full-body radiographs to try to rule out any metastasis or other obvious neoplasia, and then consider surgical removal and biopsy of the mass. I've read that it can be helpful to follow-up with I131 treatment after excision of a thyroid carcinoma, so I would speak to the owner about referral for that. Does that sound like a reasonable course of action to you or are there other things you would recommend doing first?

Thank you very much for any help or advice you can give me on this cat.

My Response:

There are many ways you could go in your workup of this cat. Most cats that I see who are loosing weight while on treatment with methimazole have high serum T4 concentrations, which can explain the weight loss. Obviously, that's not the case here, which makes this cat more interesting!

Large goiter in hyperthyroid cat

Many cats (in fact, probably nearly all hyperthyroid cats) will have an increase in goiter size with time; that makes sense since we aren't inhibiting thyroid tumor growth with the methimazole. We are only blocking thyroid hormone secretion with the drug.

Recently, a paper was published showing that on thyroid biopsy, some cats with long-standing hyperthyroidism had evidence of transformation of thyroid adenoma to carcinoma. I do believe that this happens more than we realize, and I now see almost a cat a month with thyroid carcinoma. Almost all cats with thyroid carcinoma that I see have been on methimazole for longer than 2 years.

So in your cat, the enlargement of the thyroid mass could indicate that the tumor has simply grown larger with time, or it could indicate malignant transformation. As you indicated, thyroid biopsy would be helpful in making that diagnosis. Many of these cats have extension or metastasis into the thoracic cavity so you might not be able to cure that cat with surgical thyroidectomy if that is the case. What I like to do in that situation is to perform a thyroid scan (thyroid scintigraphy) prior to surgery, which would tell us where the thyroid tumor tissue is located and help direct what needs to be removed or biopsied, if the cat does go to surgery.

That all said, why is your cat loosing weight despite a normal serum T4? With the polyphagia, the cat should be taking in enough calories. If there vomiting or diarrhea? (I am guessing no diarrhea because of the constipation.) Cats with weight loss that are eating normally must have either increased loss of glucose in the urine or impaired absorption of nutrients from the GI tract. To that end, I would recommend that you perform an abdominal ultrasound, in addition to your full-body x-rays, prior to either thyroid biopsy or thyroid scintigraphy. Urine culture should also be considered to exclude pyelonephritis.

As far as other hormones being secreted, I'd suggest that you also measure a serum free T4 and T3 concentration on this cat. It's possible that the serum concentrations of free T4 or T3 are still high and that could explain some of the cat's weight loss.

References:

1) Harvey AM, Hibbert A, Barrett EL, Day MJ, Quiggin AV, Brannan RM, Caney SM. Scintigraphic findings in 120 hyperthyroid cats. J Feline Med Surg. 2009 11:96-106.

Źródło: endocrinevet.blogspot.com

I have a 10-year-old male neutered diabetic chihuahua that was diagnosed after Vetsulin went off the market. We tried for several months to regulate him on Humulin N, but we never could get him controlled.

We finally got him enrolled in the Vetsulin Critical Need Program. He is doing great on Vetsulin given twice daily, but now we're unable to get any more of the Vetsulin. As you know, the Vetsulin Critical Need's Program has been discontinued!

Now that that honeymoon is over, what insulin can I try on this problem diabetic?

My Response:

Vetsulin (Lente insulin) is actually a mixture of rapid-acting and long-acting insulins (Semi-lente and Ultralente). So knowing that your patient responded better to the Vetsulin, you have 3 'general' choices for selecting the next insulin preparations in this dog. I do not believe that Vetsulin will be returning to the market anytime soon. You also know from past experience that human NPH isn't a good choice for this diabetic patient.

Humulin 70/30 (Eli Lilly) may be a good choice in this dog. This is a 100 U/ml pre-mixed combination of 30% short-acting and 70% intermediate-acting insulin. Because it has a similar duration/action curve to Vetsulin, Humulin 70/30 insulin is well suited to a twice-daily dosing regimen in diabetic dogs where meals are fed at the same time as the insulin injections.

Another insulin choice similar to Humulin 70/30, is a pre-mixed combination of a short-acting synthetic insulin analogue (ie, Lispro or Aspart insulin) with a longer-acting insulin analogue (ie. Lispro or Aspart Protamine Insulin). Examples of these synthetic insulin combinations include Humalog Mix 75/25 (Eli Lilly) or NovoLog 70/30 (Novo Nordisk). Both of these insulin analogue mixtures are given twice daily with meals.

Finally, my third choice is detemir insulin (Levemir, Novo Nordisk). This is another insulin analogue with a long duration of action with a similar action profile to glargine (Lantus), but detemir appears to be more potent and work better in dogs than than glargine does. Detemir is the most potent of these insulin choices and is dosed initially at 0.1 U/kg BID, again generally administered at time of feeding.

Źródło: endocrinevet.blogspot.com

My response:

All of your questions are good ones, and I wish I had the answers! You are correct that Cushing's disease is very common in dogs but extremely rare in people. We do not know why but this has been the case for many years, and it is highly unlikely that stress or over-vaccination plays a role in the canine disease.

Most of these dogs (and people) with Cushing's disease have a small pituitary tumor. In both dogs and people, these pituitary adenomas are monoclonal neoplasms, but why they develop remain unclear.

And finally, you are right about the cost. This is a very expensive disease, both in the diagnosis of the disease as well as the long-term treatment. All of the treatments for Cushing's disease in dogs, which include (1) medical (mitotane or trilostane), (2) surgery hypophysectomy (i.e., removal of the pituitary) or adrenalectomy (i.e., removal of one or both adrenal glands), or (3) pituitary radiation are extremely costly.

Hopefully, we will be able to make some progress in the pathogenesis and develop better and less expensive treatments in the near future.

Źródło: animalendocrine.blogspot.com

Even though hypothyroidism is the most frequently recognized canine endocrine disorder in dogs, it is still difficult to make a definitive diagnosis of the condition. Since the thyroid gland regulates metabolism of all of the body’s cellular functions, reduced thyroid function can produce a wide range of clinical signs (see our last blog post). Many of these signs mimic those of other disorders and illnesses, making recognition of a thyroid condition and proper interpretation of thyroid function tests confusing and problematic for veterinarians.

The dog’s signalment can be important!

The first step in diagnosis of hypothyroidism is to review the dog’s signalment (i.e., age and breed). Most hypothyroid dogs are young adults, and certain breeds are predisposed to developing the condition (see our last last blog post on this topic). That said, we can see hypothyroidism in any breed of dog, and very young or old dogs may also be affected.

Dog’s history, clinical signs, and physical examination findings

Another part of how we diagnose is a review of the history, and clinical symptoms the dog with suspected hypothyroidism is exhibiting. The most common clinical features include mental dullness or lethargy, weight gain, and skin changes. (See our last blog post for a list of clinical signs and images of affected dogs)

General laboratory evaluation

All dogs with suspected hypothyroidism should have a general laboratory panel done prior to determination of any specific thyroid function tests. Ideally, this should include a complete blood count (CBC), comprehensive serum chemistry panel, and complete urinalysis.

• Complete blood count (CBC) – It is not uncommon for hypothyroid dogs to be anemic (normocytic, normochromic, nonregenerative anemia).

• Serum chemistry profile – Hypothyroid dogs have decreased fat metabolism and commonly have high levels of blood cholesterol (hypercholesterolemia) and lipids (hyperlipidemia).

• Serum chemistry profile – Hypothyroid dogs have decreased fat metabolism and commonly have high levels of blood cholesterol (hypercholesterolemia) and lipids (hyperlipidemia).

• Urinalysis – A complete urine analysis is important for assessing whether other diseases are affecting your dog either in addition to, or instead of hypothyroidism. This test is normal in hypothyroid dogs.

Although we frequently see changes in the general laboratory work that point to hypothyroidism as a cause of the dog’s clinical signs, the most important reason that we must do these test in to rule out other diseases that may mimic hypothyroidism. Many common non-thyroid diseases (e.g., diabetes, Cushing’s syndrome, kidney or heart disease, severe infections) can also cause circulating thyroid hormone levels in the blood to decrease.

Your veterinarian must perform these general lab tests to rule these diseases out before confirming a diagnosis of hypothyroidism.

Once these general laboratory tests have been done, the next step in diagnosis is to run one or more specific thyroid tests. That will be the topic of my next blog post.

Źródło: animalendocrine.blogspot.com

Because of the vague clinical signs and the absence of specific abnormalities on a routine blood test, the diagnosis should be confirmed through a specific evaluation of the thyroid gland. As always, laboratory results should be interpreted in the light of history and physical examination findings. A thorough clinical examination of the patient, knowledge of the advantages and disadvantages of all available tests and knowledge of the factors that can influence the results, will allow the veterinarian to correctly diagnose the disease.

In dogs with suspected hypothyroidism, the clinical suspicion of the disease is obtained by reviewing the dog’s signalment, history, and clinical features. A general blood screening examination, including a CBC, comprehensive chemical panel, and complete urinalysis are next done to look for changes consistent with hypothyroidism and exclude other problems that mimic hypothyroidism.

If hypothyroidism is still suspected, the diagnosis should be confirmed through a specific evaluation of the thyroid gland function. These tests include measurement of serum concentrations of total and free T4, T3, and TSH. The choice of diagnostic test(s) performed are based heavily on the index of suspicion for hypothyroidism.

In some dogs, it may also be necessary to use thyroid scintigraphy to definitely confirm the condition. However, most veterinary offices do not have the equipment needed to do this thyroid scanning procedure.

Thyroid specific evaluation

Total thyroxine (T4)

This test usually used as the initial thyroid specific screening test. If the results of this test are within normal limits, your veterinarian will usually look for other causes of your dog’s clinical signs. Most dogs with hypothyroidism will have low values for T4 compared with healthy dogs. However, dogs that have other diseases can also have low T4, so false-positive T4 results are commonly observed. Again, that is why general laboratory testing must be done in all dogs with suspected hypothyroidism.

This test measures the total amount of thyroxine (abbreviated T4, because it contains 4 iodine molecules) which is the main hormone produced by the thyroid gland. hormone circulating in the blood, which includes both bound and unbound T4 molecules. More than 99% of T4 hormone is “bound,” meaning that it is attached to proteins in the blood, making the bound T4 too big to pass from the circulation into the tissues. A T4 result by itself is can be misleading, inasmuch as it is affected by anything that changes the amount of binding proteins circulating in the blood, such as occurs with drugs and nonthyroidal illness.

This test measures the total amount of thyroxine (abbreviated T4, because it contains 4 iodine molecules) which is the main hormone produced by the thyroid gland. hormone circulating in the blood, which includes both bound and unbound T4 molecules. More than 99% of T4 hormone is “bound,” meaning that it is attached to proteins in the blood, making the bound T4 too big to pass from the circulation into the tissues. A T4 result by itself is can be misleading, inasmuch as it is affected by anything that changes the amount of binding proteins circulating in the blood, such as occurs with drugs and nonthyroidal illness.

Certain kinds of drugs (e.g. sulfa antibiotics, anti-inflammatory, anti-depressant and anti-seizure medication) can cause artificially lowered thyroid levels so it is important to make sure we account for these before making a diagnosis.

In addition, although normal T4 reference levels of healthy adult dogs tend to be similar for most breeds, they do vary depending on age and breed. Puppies, for example, display higher T4 levels than adult dogs, because their bodies need extra hormones as they undergo the maturation process. Compared to the adult dog “normal range,” the optimal thyroid levels for puppies are normally in the high-normal to slightly high range. Conversely, the basal metabolism of geriatric dogs is usually slowing, so optimal T4 levels are likely to be closer to midrange or even slightly lower. Similarly, giant breed dogs have lower basal T4 levels, and Sight hounds as a group have the lowest T4 levels of all the breed categories.

Free T4

Serum free T4 represents the tiny fraction (< 0.1%) of total T4 that is unbound and therefore is biologically active and able to enter the tissues. Since protein levels in the blood do not (or only minimally) affect free T4, it is considered a more accurate test of true thyroid activity than the total T4. Free T4 is much less likely to be influenced by nonthyroidal illness or drugs.

Both total T4 and free T4 are lowered in almost all dogs of hypothyroidism. While most endocrinologists favor the equilibrium dialysis method for measuring free T4, newer technologies offer alternative and accurate assays that are faster and less costly.

Overall, this is a more sensitive indicator of hypothyroidism. Some dogs that are not truly hypothyroid may have a low total T4 but a normal free T4.

Total T3

Measuring serum T3 alone is not considered an accurate method of diagnosing hypothyroidism, as this hormone reflects tissue thyroid activity and is often influenced by concurrent nonthyroidal illness. It is, however, useful as part of a thyroid profile or health screening panel.

Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH)

Production of thyroid hormones is regulated by the pituitary gland, through a hormone called thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). A feedback loop exists between the body and the pituitary gland, with TSH production by the pituitary going up when the body needs thyroid hormone and turning off when thyroid hormone levels are high.

Therefore, dogs with primary hypothyroidism are expected to have high serum TSH concentrations. Unfortunately, the current TSH test used in dogs is associated with a high incidence of false-negative or false-positive results.

Result for serum TSH must be evaluated together with serum T4 (and free T4) concentrations. Finding a low T4, low free T4, and a high TSH concentration is diagnostic for canine hypothyroidism. On the other hand, finding a high TSH level together with normal values for T4 or free T4 does not confirm hypothyroidism and is best ignored (at least for the time being).

Thyroglobulin autoantibody levels

High titers of thyroglobulin autoantibodies are present in the serum of dogs with autoimmune thyroiditis, which is the heritable form of hypothyroidism. Performing this test is especially important in screening breeding stock for autoimmune thyroiditis, as dogs testing positive for thyroglobulin autoantibodies should not be bred.

This is not in any way a stand-alone test for hypothyroidism and evaluation of additional tests is necessary to determine whether a dog is hypothyroid.

Thyroid Scintigraphy (Scanning)

Thyroid scintigraphy provides valuable information regarding both thyroid anatomy and physiology and can play an integral role in the diagnosis of thyroid disease in dogs or cats. Although rarely used to diagnose hypothyroidism, is now clear that thyroid imaging is also the best way to confirm the diagnosis of that common disorder. At the Animal Endocrine Clinic, we have the equipment needed to perform thyroid scintigraphy and we readily use this in the diagnosis of dogs and cats with thyroid disease. For more information about thyroid scans, please visit our Nuclear Imaging Facebook page.

In normal dogs, the thyroid gland appears on thyroid scans as two well-defined, focal (ovoid) areas of uptake in the cranial to middle cervical region. The two thyroid lobes are symmetrical in size and shape and are located side by side. Activity in the normal thyroid closely approximates activity in the salivary glands, with an expected “brightness” ratio of 1:1.

In dogs with hypothyroidism, thyroid scanning typically reveals decreased or even absent thyroid uptake (thyroid gland is not at all visible on the scan). In contrast, dogs that have falsely low serum thyroid hormone concentrations secondary to illness or drug therapy have a normal thyroid image.

Źródło: animalendocrine.blogspot.com

There is no cure for hypothyroidism, but it is a disease that is easily managed.

The foundation of treatment of dogs with hypothyroidism is thyroid hormone replacement therapy. In other words, we simply replace the missing hormone to restore the dog’s metabolic function back to normal.

However, it’s important that the dog receives the proper thyroid hormone supplement that is given at the appropriate dosage and at the correct intervals to best resolve all of the clinical signs of hypothyroidism.

Thyroid hormone replacement therapy: Which product do we use?

Treatment for hypothyroidism involves lifelong oral medication with levothyroxine (L-T4), a relatively inexpensive synthetic thyroid hormone supplement. These treatments have to be given by mouth, and the supplements are available both as tablets and a liquid formulation. It is important to give the medication at the same time every day (preferably twice daily), and it’s been shown that absorption is better if given on an empty stomach.

Why give L-T4 as the thyroid hormone replacement? As discussed in our last post, thyroxine (abbreviated T4, because it contains 4 iodine molecules) is the hormone produced by the thyroid gland. It is converted primarily in the liver and kidney by an enzyme (deiodinase enzyme) that removes one of the iodine molecules, thereby forming the T3 hormone, which enters the cells. Its function is to regulate the body’s metabolism. So by giving L-T4, this will be automatically metabolized to all of the other forms of thyroid hormone made in a dog’s body.

Administering thyroid hormone replacement therapy

How and when you administer your dog's thyroid medication will have a tremendous impact on the success of the treatment.

First of all, it is extremely important that the thyroid hormone treatment not be given with food. It is best to administer thyroid medication at least 1 hour before the dog’s meal or at least 3 hours after eating. Many veterinarians are not aware of the fact that absorption of thyroid hormone from the gut is much better when the hormone is given on an empty stomach.

Thyroxine is best given twice per day, in the morning and evening, spaced about 12 hours apart. Dividing the medication into two doses ensures that the dog receives a steady state of thyroid hormone throughout the day, rather than experiencing very high levels shortly after administration and low levels later in the day when only a morning dose is given.

Although most L-T4 medication comes in pill form, there is a liquid available (Leventa; see figure above) that the company suggests just one dose per day. However, I still recommend that the liquid medication be given twice daily for the best results. If your dog is taking liquid L-T4, be sure to discuss the dosing with your veterinarian.

Monitoring the hypothyroid dog’s L-T4 dosage

Regular follow-up blood tests are vital to ensure your dog receives the accurate amount of hormone replacement therapy. Generally blood tests are rechecked approximately 4 to 8 weeks after starting medication and again as needed while the dog’s metabolism adjusts to the therapy. After that, once yearly checks are adequate to ensure that the thyroid hormone level remains in the normal range.

When taken as directed, thyroxine is extremely safe. However, it is important to make sure your dog is receiving the proper dosage based on the variables discussed above, since excessive thyroxine intake can lead to thyrotoxicosis (thyroxine overdose), a condition that needs to be promptly addressed by your veterinarian. Common signs of L-T4 overdosage include excessive thirst and urination, panting, restlessness, and pacing. If this occurs, the L-T4 needs to be stopped for a day or two and the daily dosage lowered accordingly.

Prognosis for canine hypothyroidism With proper treatment, the long-term prognosis is excellent. However, complete resolution of clinical features of hypothyroidism may take several weeks to months in some dogs.

Źródło: animalendocrine.blogspot.com

Hypothyroidism is the condition where the thyroid gland does not produce enough of the thyroid hormones T3 and T4. When levels of these hormones are low, it slows metabolism.

Causes of hypothyroidism in cats

In contrast to dogs, where hypothyroidism is one of the most commonly diagnosed hormonal disorders, naturally-occurring hypothyroidism is extremely rare in cats. When it does occur, it is most common in young cats that are born with the disorder.

In older cats, hypothyroidism is usually caused as a complication of treatment for hyperthyroidism. Hypothyroidism may develop after surgically removing a thyroid tumor, destroying it with radioiodine, or by administering antithyroid drugs as a treatment for hyperthyroidism.

Clinical features seen in cats with hypothyroidism

Because deficient thyroid hormone affects the function of all organ systems, the signs of hypothyroidism vary. In cats, signs include lethargy, loss of appetite, hair loss, low body temperature, and occasionally decreased heart rate.

Obesity may develop, especially in older cats that become hypothyroid after treatment of hyperthyroidism. In cats that are born with hypothyroidism (or that develop it at a young age), signs include dwarfism, severe lethargy, mental dullness, constipation, and decreased heart rate.

Diagnosing feline hypothyroidism

To accurately diagnose hypothyroidism, one must first closely evaluate the cat’s clinical signs and routine laboratory tests to rule out other diseases that affect thyroid hormone testing.

The veterinarian must confirm the diagnosis using one more specific thyroid function tests. Like dogs with suspected hypothyroidism, these tests may include serum total T4, free T4, or TSH levels.

In some cases, a TSH stimulation test or thyroid imaging (scintigraphy) is necessary for diagnosis.

Treating cats with hypothyroidism

Hypothyroidism is easily treatable; it only requires synthetic thyroid hormone supplements (L-thyroxine or L-T4). The success of treatment can be measured by the amount of improvement in clinical signs. Your veterinarian will have to monitor the thyroid hormone level to determine whether the thyroid hormone supplement dose is correct. Once the dose has been stabilized, thyroid hormone levels are usually checked once or twice a year. Treatment is generally life-long, but the prognosis is excellent.

Źródło: animalendocrine.blogspot.com