University of Georgia researchers, studying more than 75,000 dogs from 82 breeds, have found that the causes of canine deaths vary by breed as well as age (1). The study revealed that congenital diseases, trauma and infection are the most frequent causes of deaths in dogs under 2 years old and that cancer risk peaks at about age 10.

The researchers also determined that bigger dog breeds are more vulnerable to musculoskeletal disease, gastrointestinal disease, and cancer. Smaller breed dogs, on the other hand, are more at risk for endocrine and metabolic diseases such as diabetes mellitus and Cushing's disease(1).

Rosie, an 11-year old Bichone Frise with both diabetes and Cushing's disease. The photo on the left is before treatment, whereas the photo on the right is after successful treatment of the Cushing's disease and diabetes.

It has long been recognized that there are patterns in the causes of death for our dogs. This study helps owners know what sort of problems to watch out for in their pets. It helps veterinarians focus on the most likely cause of a particular dog’s illness. And most importantly it guides us in identifying specific risks for individual patients and taking action to minimize these and prevent or delay illness and death.

1. Fleming JM, Creevy KE, Promislow DEL. Mortality in North American Dogs from 1984 to 2004: An Investigation into Age-, Size-, and Breed-Related Causes of Death. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 2011; 25: 187-198.

Źródło: animalendocrine.blogspot.com

High levels of toxic flame-retardant chemicals including polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDE's) were measured in the blood of 18 pet dogs. The measured concentrations of these toxic chemicals were up to 10 times higher as those generally found in humans, according to research published in the journal Environmental Science and Technology (1).

High levels of toxic flame-retardant chemicals including polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDE's) were measured in the blood of 18 pet dogs. The measured concentrations of these toxic chemicals were up to 10 times higher as those generally found in humans, according to research published in the journal Environmental Science and Technology (1).

The PBDE compounds are widely used as flame retardants in household furniture and electronics equipment; these chemicals are known to migrate out of the products and enter the environment.

Researchers suggest that pets may act as "biosentinels" for humans who live with them in the same home. "Even though they've been around for quite awhile, we don't know too much about these compounds' toxicological effects on humans or animals," said research scientist Marta Venier (2).

A previous study from the same laboratory showed that pet cats also had much higher serum levels of flame retardants compared to humans, despite sharing the same household environment (3). It has been postulated that these high PBDE levels may contribute to the development of thyroid tumors and hyperthyroidism in cats.

Dogs, in contrast to cats, could be expected to have lower serum levels of flame retardants because they are metabolically better equipped to degrade these compounds. Thus, dogs might be more similar to humans in their response to these environmental chemicals and be better indicators of human exposures to these contaminants.Thus, it was surprising to find the high levels of these toxic compounds in these dog blood samples.

References:

Venier M, Hites RA. Flame retardants in the serum of pet dogs and in their food. Environ Sci Technol. 2011 Article ASAP DOI:10.1021/es1043529

Science News. Toxic Chemicals Found in Pet Dogs.

Dye JA, Venier M, Zhu L, Ward CR, Hites RA, Birnbaum LS. Elevated PBDE levels in pet cats: sentinels for humans? Environ Sci Technol. 2007;41:6350-6356.

Źródło: animalendocrine.blogspot.com

Hypoadrenocorticism, also called adrenal insufficiency or Addison’s disease, is a disorder in which the adrenal gland does not produce sufficient adrenal hormones that are essential for life. When the adrenal glands fail, the consequences are very severe. Untreated, hypoadrenocorticism may lead to death.

Hypoadrenocorticism, also called adrenal insufficiency or Addison’s disease, is a disorder in which the adrenal gland does not produce sufficient adrenal hormones that are essential for life. When the adrenal glands fail, the consequences are very severe. Untreated, hypoadrenocorticism may lead to death.

Fortunately, naturally occurring hypoadrenocorticism is extremely rare in cats, with less than 25 cases reported. However, the disease is generally missed because veterinarians rarely consider this problem as a differential diagnosis in cats.

A much more common reason that cats develop hypoadrenocorticism is long-term treatment with steroids for a variety of dermatologic or behavioral reasons. These cats do not show signs of adrenal insufficiency unless the mediation is stopped too abruptly. This is also known as iatrogenic hypoadrenocorticism (see, "What causes this disease in cats," below).

What are the missing hormones in cats with hypoadrenocorticism?

Like dogs or people with Addison’s disease, cats with hypoadrenocorticism are unable to produce one or two steroid hormones, both secreted from the adrenal cortex (outer layer of the adrenal gland).

- The first hormone that's missing is cortisol, which is very important in maintaining a normal metabolism, as well as a general sense of well-being.

- The second hormone that's missing is aldosterone, which manages the water balance and serum electrolytes in the body.

What are the different forms of hypoadrenocorticism in cats?

Hypoadrenocorticism can be divided into primary and secondary subtypes:

- With primary hypoadrenocorticism (Addison's disease), the problem lies in the adrenal gland itself, with atrophy or destruction of the gland.

- With secondary hypoadrenocorticism, the adrenal glands are normal, and the problem lies in the pituitary gland. The pituitary gland normally secretes a hormone called ACTH (adrenocorticotropic hormone) that stimulates the adrenal gland to secrete its hormones. In secondary hypoadrenocorticism, ACTH is not secreted in needed amounts, leading to the secondary adrenal insufficiency.

What causes this disease in cats?

In most cats with naturally occurring hypoadrenocorticism, the exact cause for the adrenal failure is never known for certain.

Many cats, however, develop the problem because of iatrogenic causes. The term iatrogenic means that the disease is caused by, or results from, a medical or surgical treatment for another problem (i.e., the disease did not develop spontaneously). In cats with primary hypoadrenocorticism, the following causes must be considered.

- Most cats that develop Addison’s disease spontaneously appear to have an autoimmune condition in which the body destroys part of the adrenal cortex.

- Infiltrative conditions such as lymphoma (a form of cancer) can destroy the adrenal gland to cause Addison’s disease.

- Surgical removal of both adrenal glands for treatment of feline Cushing’s disease will result in iatrogenic Addison’s disease, but this is a rarely used operation for cats.

- Rarely, primary adrenal failure can occur secondary to trauma. This may be temporary or permanent.

In cats with secondary hypoadrenocorticism, the following underlying causes should be excluded. Again, all of these conditions are associated with deficient secretion of the pituitary hormone, ACTH.

Congenital deficiency of ACTH secretion (not yet reported in cats).

Pituitary tumors, inflammation, or trauma that have destroyed most of the ACTH-secreting cells in the pituitary gland, leading to deficient ACTH secretion.

Iatrogenic hypoadrenocorticism that results from administration of large doses of cortisone-like hormones (glucocorticoids or progesterone-like drugs), which are then withdrawn too rapidly. In this case, the term iatrogenic means that the hypoadrenocorticism is caused by the high-dose glucocorticoid or progestin (megestrol acetate; trade names, Ovaban or Megace) treatment.

Chain of events leading to severe hypoadrenocorticism in cats

With primary hypoadrenocorticism (Addison's disease), cats develop complete adrenocortical destruction with both cortisol and aldosterone deficiencies.

Aldosterone is the main mineralocorticoid hormone, and it affects the levels of potassium, sodium, and chloride in the blood. Low levels of aldosterone cause potassium to gradually build up in the blood and, in severe cases, cause the heart to slow down or beat irregularly. Some cats have such a slow heart rate (50 beats per minute or lower) that they can become weak or go into shock.

More commonly, cats will develop iatrogenic, secondary hypoadrenocorticism (see above, What causes this disease in cats) to treatment with steroid-like drugs used for anti-inflammatory purposes. This subgroup of hypoadrenal cats is only deficient in cortisol and maintains a normal aldosterone level. These cats are more difficult to diagnose because their signs are milder and the serum potassium, sodium, and chloride values all remain normal.

What are the clinical signs and symptoms of feline hypoadrenocorticism?

Signs of hypoadrenocorticism may include repeated episodes of vomiting and diarrhea, loss of appetite, dehydration, and gradual, but severe, weight loss.

Because the clinical signs of hypoadrenocorticism are vague and nonspecific, it can be difficult to diagnose in the earlier stages of disease. Therefore, severe consequences, such as shock and evidence of kidney failure, can develop suddenly in some cats with complete adrenocortical destruction.

In cats with secondary hypoadrenocorticism, the clinical signs generally are not as severe and are usually not life threatening.

How is feline hypoadrenocorticism diagnosed?

How is feline hypoadrenocorticism diagnosed?

A veterinarian may suspect hypoadrenocorticism based on the cat’s history (including past treatment with steroids or progestins), clinical signs, and certain laboratory abnormalities, such as low serum sodium and high potassium concentrations. However, one must specifically evaluate adrenal function to document low cortisol levels to definitively diagnose hypoadrenocorticism.

The diagnosis of hypoadrenocorticism is confirmed by lack of cortisol response to ACTH administration. It is important to recognize that the reference range for the post ACTH cortisol is lower in cats than in dogs. To confirm a diagnosis of hypoadrenocorticism, however, the serum concentrations of both the basal cortisol level and ACTH-stimulated cortisol levels are low (generally less than 2 µg/dl).

How is primary hypoadrenocorticism (Addison’s disease) treated?

How is primary hypoadrenocorticism (Addison’s disease) treated?

Untreated, primary hypoadrenocorticism (Addison’s disease) can lead to an adrenal crisis. An adrenal crisis is a medical emergency that requires intravenous fluids to restore the body’s levels of fluids, salts, and sugar to normal. Once stabilized, the cat can then be treated with hormone replacement therapy (either orally or by injection). With proper treatment, the long-term prognosis is excellent.

Long-tem treatment of primary hypoadrenocorticism (Addison’s disease) includes treatment with either both missing adrenal hormones. For mineralocorticoid replacement, either oral fludrocortisone (trade name, Florinef) or injectable desoxycortisone privalate (DOCP, trade name, Percorten) are given. In cats, glucocorticoid replacement is best given as oral or injectable prednisolone.

Response to treatment is similar although clinical signs such as anorexia, lethargy, and weakness may sometimes take longer to resolve than in dogs. Prognosis for long-term survival is good with the exception of cats in which the underlying cause is adrenal neoplasia.

How is iatrogenic hypoadrenocorticism (secondary to overtreatment with steroids or progestins) treated?

In cats with iatrogenic hypoadrenocorticism due to overtreatment with steroids for nonendocrine problems, treatment simply involves reinstituting glucocorticoid replacement at a gradual tapering dosage over weeks to months. This allows the pituitary ACTH-secreting cells to recover and stimulate normal cortisol secretion once again.

Źródło: animalendocrine.blogspot.com

The Animal Endocrine Clinic recently partnered with Anjellicle Cats Rescue and Ready for Rescue animal shelters to provide radioactive iodine treatment to two hyperthyroid cats. The success of the advanced medical treatment, pioneered by Dr. Peterson, will allow the cats a chance at being adopted into new homes.

The Animal Endocrine Clinic recently partnered with Anjellicle Cats Rescue and Ready for Rescue animal shelters to provide radioactive iodine treatment to two hyperthyroid cats. The success of the advanced medical treatment, pioneered by Dr. Peterson, will allow the cats a chance at being adopted into new homes.

Molly, a 15 year old cat was removed from the Animal Care & Control of NYC’s “kill list” by the Anjellicle Cats Rescue. Despite the fact that Molly had become very thin and had the typical increased appetite, common to hyperthyroid cats, the rescue felt that they could find her a home. A “foster mother” with the shelter, Margaret Cozzo had heard of Dr. Peterson’s Animal Endocrine Clinic and reached out to him for help with the cat’s disease.

Said the Director of Anjellicle Cats Rescue, Kathryn Willis, “We are very pleased with the success of the treatment that Molly received at the Animal Endocrine Clinic. She has regained the weight and the spirit that she had lost while sick. She has a great disposition and will make a lovely pet for anyone.”

Foxy, a nine year old Tabby, was another cat that was saved from the “kill list” by the organization, Ready for Rescue. Foxy was also small and underweight as a result of her hyperthyroid condition. Initially treated with the daily medication, Methimazole, she experienced bad side effects. Looking for a better option, her “foster mother,” volunteer Karin Felix-Faure, had lived near the Animal Endocrine Clinic’s Manhattan location and sought out Dr. Peterson’s expertise.

Dr. Mark Peterson treated both cats at the Animal Endocrine Clinic using the most advanced medical diagnostics and treatments available for feline hyperthyroidism. Using nuclear imaging, he confirmed that both cats were hyperthyroid and then treated them with radioiodine treatment. Donations and discounts from the AEC helped pay for the cats’ treatments.

“We almost lost Foxy because she couldn’t handle the daily medication,” said Doug Halsey of Ready for Rescue. “If it hadn’t been for Dr. Peterson’s advanced treatment, Foxy would not be alive today. How cruel it would have been for her to have been removed from the ‘kill list’ and then die while receiving treatment.”

Dr. Peterson offered, “Radioactive iodine treatment is the home humane and efficient way to cure Hyperthyroidism, a common disease in cats. If left untreated, it can lead to death. We were thrilled to be able to provide these cats with a second chance at being loved and cared for in new homes. One subcutaneous treatment was all that was needed to cure both cats.”

About Anjellicle Cats Rescue:

Anjellicle Cats Rescue is an all-volunteer, not-for-profit 501(c)(3) organization. The rescue is also a member of the Mayor’s Alliance for NYC’s Animals and a New Hope Partner with the New York Animal Care & Control (ACC). The rescue has a no-kill policy and holds adoption events throughout New York City and in Connecticut. For more information about Anjellicle Cats Rescue visit http://www.anjelliclecats.com/

About Ready for Rescue:

Ready for Rescue is a New York City-based animal rescue group dedicated to saving at risk animals with a focus on cats and dogs who are suffering in the New York City shelter system. The shelter shows cats and dogs up for adoption at The Pet Health Store in Manhattan on Sundays, Noon – 4pm. For more information about Ready for Rescue visit http://ready4rescue.org/ About The Animal Endocrine Clinic: The Animal Endocrine Clinic (AEC) is a specialized veterinary practice that diagnoses and treats cats and dogs with endocrine (hormonal) disorders. AEC has three divisions:

- Hypurrcat exclusively treats hyperthyroid cats with radioactive iodine;

- The AEC's Endocrine Clinic is dedicated to diagnosing and treating dogs and cats with endocrine disorders, such as diabetes or Cushing’s disease; and

- Nuclear Imaging for Animals is a state-of-the-art medical imaging facility that performs nuclear scanning to diagnose thyroid, bone, liver, and kidney diseases in dogs and cats.

AEC has clinics in Manhattan and Westchester County and treats clients in New York City, Long Island, Westchester County, New Jersey and Connecticut. It is the only practice of its kind in the United States. For more information about AEC visit www.animalendocrine.com. Link to Press Release:

http://www.pr.com/press-release/317450

Źródło: animalendocrine.blogspot.com

Bailey is a 14-year-old male neutered domestic short hair who was diagnosed with hyperthyroidism by another veterinarian about 3 years ago and has been on methimazole since then. He also has a history of chronic constipation that has been well controlled in the last year on enulose (Lactulose) only.

Bailey is a 14-year-old male neutered domestic short hair who was diagnosed with hyperthyroidism by another veterinarian about 3 years ago and has been on methimazole since then. He also has a history of chronic constipation that has been well controlled in the last year on enulose (Lactulose) only.

I last saw Bailey a year ago, at which point he was doing well clinically but had lost about 1 lb. since his last check. At that time, he was on 5 mg of methimazole BID. A geriatric profile at that time showed a total T4 of 3.3 µg/dl, a normal CBC and serum chemistry profile (creatinine = 1.5 mg/dl, BUN = 23 mg/dl), and a urine specific gravity of 1.065. I recommended increasing his dose of methimazole to 7.5 mg in the morning and 5 mg in the evening and rechecking in 4-6 weeks.

The owner did increase the daily methimazole dose but did not follow up with us until now. Bailey has lost an additional 3 lbs. since his last exam and has developed polyphagia, polyuria, and polydipsia over the last month.

On exam yesterday, the cat now has a fairly large mass in his left ventral neck area (about 3-4 cm, slightly firm and irregular), which I had not noted on the last exam. His blood work from yesterday showed a T4 of 1.9 µg/dl, and very normal renal function (serum creatinine = 1.1 mg/dl; BUN = 22 mg/dl, USG =1.030).

So, I'm suspicious that the thyroid mass is or has become a carcinoma at this point. But would you expect the cat to lose weight secondary to a thyroid carcinoma even if the T4 is within normal range? Could it be secreting another hormone to cause the weight loss?

I thought I should recommend full-body radiographs to try to rule out any metastasis or other obvious neoplasia, and then consider surgical removal and biopsy of the mass. I've read that it can be helpful to follow-up with I-131 treatment after excision of a thyroid carcinoma, so I would speak to the owner about referral for that.

Does that sound like a reasonable course of action to you or are there other things you would recommend doing first? Thank you very much for any help or advice you can give me on this perplexing case.

My Response:

There are many ways you could go in your workup of this cat. Most cats that I see who are loosing weight while on treatment with methimazole have high serum T4 concentrations, which can explain the weight loss. Obviously, that's not the case here, which makes this cat more interesting!

Many cats (in fact, probably nearly all hyperthyroid cats) will have an increase in goiter size with time — that makes sense since we aren't inhibiting thyroid tumor growth with the methimazole. We are only blocking thyroid hormone secretion with the drug.

Recently, a paper was published showing that on thyroid biopsy, some cats with long-standing hyperthyroidism had evidence of transformation of thyroid adenoma to carcinoma (1). I do believe that this happens more than we realize, and I now see almost a cat a month with thyroid carcinoma. Almost all cats with thyroid carcinoma that I see have been on methimazole for longer than 2 years.

So in your cat, the enlargement of the thyroid mass could indicate that the tumor has simply grown larger with time, or it could indicate malignant transformation. As you indicated, thyroid biopsy would be helpful in making that diagnosis. Many of these cats have extension or metastasis into the thoracic cavity so you might not be able to cure that cat with surgical thyroidectomy if that is the case. What I like to do in that situation is to perform a thyroid scan (thyroid scintigraphy) prior to surgery, which we certainly could do in this cat. This will tell us where the thyroid tumor tissue is located and help direct what needs to be removed or biopsied, if the cat does go to surgery.

Thyroid Scan of cat with large thyroid carcinoma (left) compared to normal cat (right)

Notice the extension & invasion of the thyroid tumor into the thoracic cavity

(horizontal line indicates the region of the thoracic inlet)

That all said, why is your cat loosing weight despite a normal serum T4? With the polyphagia, the cat should bee taking in enough calories. If there vomiting or diarrhea? (I assume that diarrhea isn't present because of the constipation.)

Cats with weight loss that are eating normally must have either increased loss of glucose in the urine or impaired absorption of nutrients from the GIT. To that end, I would recommend that you perform an abdominal ultrasound, in addition to your full-body x-rays, prior to either thyroid biopsy or thyroid scintigraphy. Urine culture should also be considered to exclude pyelonephritis.

As far as other hormones being secreted, I'd suggest that you also measure a serum free T4 and T3 concentration on this cat. It's possible that the free T4 or T3 concentrations are still high and that could explain some of weight loss in this cat.

Reference:

1. Hibbert A, Gruffydd-Jones T, Barrett EL, Day MJ, Harvey AM. Feline thyroid carcinoma: diagnosis and response to high-dose radioactive iodine treatment. J Feline Med Surg. 2009 11:116-24.

Źródło: endocrinevet.blogspot.com

Rosie came to us roughly a year ago exhibiting all of the classic signs of Cushing's disease, which I covered in my last blog post:

increased thirst and urination

increased appetite

excessive panting (see photo on left)

lethargy

pot belly appearance (see photo on left)

weight gain (see photo on left)

hair loss: hair thinning on trunk, bald tail (see photo on left)

I diagnosed her as having Cushing's disease and prescribed a regimen of trilostane (Vetoryl), given at a dosage of 30 mg twice a day.

The photo on the right was taken at her one-year check up. As you can see from the photos, she's lost weight (8 pounds) as well as her pot belly. She is much more active and no longer excessively thirsty or panting.

Źródło: animalendocrine.blogspot.com

Over the past week I have received a number of questions about radiation both from pet owners and veterinarians about the danger from the nuclear fallout from Japan, not for their human families but also for their dogs and cats.

The question is: should we all be buying potassium iodide for ourselves? Should we also give this to our pets? Since dogs and cats are smaller than we are, could they be impacted by smaller amounts of radiation? What should we do?

The question is: should we all be buying potassium iodide for ourselves? Should we also give this to our pets? Since dogs and cats are smaller than we are, could they be impacted by smaller amounts of radiation? What should we do?

The answer to these questions, at least for the time being, is not to take potassium iodide or administer the drug to our pets. So far, the amount of radiation coming here from Japan has been termed negligible by our government.

What's more, potassium iodide only helps pets (or people) to deal with radioactive particles (I-131) which ultimately impact the thyroid gland, not other organs or illnesses which may result from excessive exposure to radiation. I understand that we care about our pets and want to be proactive, but we might do more harm than good by giving this iodide supplement.

How does potassium iodine work?

How does potassium iodine work?

The thyroid gland is the only tissue in the body that wants or needs iodine to perform its normal function (i.e., to make the thyroid hormones T4 and T3, both of which contain iodine in their hormone structure). As you can see, in the figure on the right, thyroxine or T4 (the main thyroid hormone secreted by the thyroid gland), contains 4 iodine groups on the hormone molecule. T3, the other main thyroid hormone, contains 3 iodine groups on the molecule.

By saturating the thyroid with stable iodide (i.e., non-radioactive iodine), potassium iodide works to block the effects of radioiodine (I-131) on the thyroid gland. In other words, if your thyroid already has all the iodine it needs it will refuse to take up the I-131.

Of course, there's a catch. Doses of potassium iodide high enough to protect your thyroid from I-131 have some nasty side effects.

What are the adverse effects of potassium iodide?

Side effects associated with administration of potassium iodide may include gastrointestinal upset, allergic reactions, skin rashes, salivary gland inflammation, hyperthyroidism, or hypothyroidism. That is a pretty impressive list of side effects!

So what should we do?

Since radioactive iodine (I-131) decays rapidly, current estimates indicate there will not be a hazardous level of radiation reaching the United States from this accident. If and when an exposure does warrant the use of potassium iodide, it should be taken as directed by physicians or public health authorities until the risk for significant exposure to radioactive iodine dissipates, but probably for no more than 1 to 2 weeks.

Again, unless the experts declare that radiation levels are high enough, we shouldn't take it or administer it to our pets. If you're determined to purchase potassium iodide for you or your pet, please beware —many legitimate outlets are sold out, particularly if you purchase the potassium iodide online.

Źródło: animalendocrine.blogspot.com

This week, one of my veterinary colleagues returned from a 3-week visit to Japan. She was obviously worried about possible radiation exposure in the aftermath of the Japan nuclear crisis and asked for my advice about how she could check for radiation contamination. I asked her to come to my office today so that I could monitor her for any radiation contamination. I have the radiation instruments in both of my offices because we routinely treat hyperthyroid cats with radioactive iodine (I-131). (See my website for more information.) My staff and I use this radiation detection equipment on a daily basis in order to check for contamination, both on our bodies and well as in our work environment (this is a safety precaution - we do NOT expect or plan on becoming contaminated!).

I first monitored by colleague by use of a general purpose survey meter (Geiger counter). With this meter, I've attached a GM (geiger-mueller) pancake detector, which is sensitive to alpha, beta and gamma radiation and is the industry standard for detecting contamination.

Fortunately, I found absolutely no detectable levels of external contamination with my measurements.

Dr. Peterson checking for external radiation contamination

We next measured my colleagues thyroid gland for internal contamination. As you may know, the principal radiation source of concern with the nuclear reactor accident in Japan is the release of radioactive iodine (I-131). This radioactive isotope that presents a special risk to health because iodine is normally concentrated in the thyroid gland. Exposure of the thyroid to high levels of radioactive iodine may lead to development of thyroid nodules and thyroid cancer years later.

Counting thyroid gland for I-131 contamination

To measure for internal (thyroid) contamination of I-131, we used a general purpose radiation scaler/ratemeter attached to a shielded well gamma radiation counter. This is a very sensitive instrument, which allows us to detect very tiny amounts of gamma radiation, including the gamma rays (photons) emitted from I-131.

Radiation counts below background readings, indicating no contamination

Fortunately, the thyroid counts measured in my college (373 counts per minute or cpm) were below the background radiation counts of 385 cpm. This demonstrated that there was NO internal thyroid radiation. Overall, we found NO external or internal contamination in my colleague. All good news! The fact that we measured a background radiation count is a normal, expected finding: background radiation is constantly present in the environment and is emitted from a variety of natural and artificial sources. See this article for more information on background radiation.

Źródło: animalendocrine.blogspot.com

Addison’s disease, also called hypoadrenocorticism, is a disorder in which the adrenal gland does not produce sufficient hormones. The adrenal  glands are essential for life. When the adrenal gland fail, the consequences are very severe.

glands are essential for life. When the adrenal gland fail, the consequences are very severe.

What are the missing hormones in Addison's disease?

Dogs with hypoadrenocorticism (Addison's disease) are unable to produce one or two steroid hormones, both secreted from the adrenal cortex (outer layer of the adrenal gland).

The first hormone that's missing is cortisol, which is very important in maintaining a normal metabolism, as well as a general sense of well being.

The second hormone that's missing is aldosterone, which manages the water balance and serum electrolytes in the body.

What are the different forms of hypoadrenocorticism?

Hypoadrenocorticism can be divided into primary and secondary subtypes.

- With primary hypoadrenocorticism (Addison's disease), the problem lies in the adrenal gland itself, with atrophy or destruction of the gland.

- With secondary hypoadrenocorticism, the adrenal gland are normal, and the problem lies in the pituitary gland. The pituitary gland normally secretes a hormone called ACTH (adrenocorticotropic hormone) that stimulates the adrenal gland to secrete its hormones; in secondary hypoadrenocorticism, ACTH is not secreted in needed amounts, leading to the secondary adrenal insufficiency.

What causes Addison's disease in dogs?

In most dogs, we cannot determine what caused their adrenal disease. With primary hypoadrenocorticism, the following causes must be considered.

- Most dogs with the primary form appear to have an autoimmune condition in which the body destroys part of the adrenal cortex

- Very rarely, infiltrative conditions such as cancer can metastasis to and destroy the adrenal gland to cause Addison’s disease

- Occasionally, treatment of Cushing’s disease with the drugs mitotane and trilostane will result in complete adrenal destruction and Addison’s disease

With secondary hypoadrenocorticism, we must rule out the following underlying causes.

Congenital deficiency of ACTH secretion

Pituitary tumors, inflammation or trauma that have destroyed most of the ACTH-secreting cells in the pituitary gland, leading to deficient ACTH secretion

Are some dogs predisposed to developing this disease?

Although hypoadrenocorticism can develop in any age, breed, or sex of dogs, the following points should be taken into consideration when making a diagnosis.

- Hypoadrenocorticism is most common in young to middle-aged dogs.

- Most dogs with Addison's disease are females.

- Bearded Collies, Standard Poodles (see photo on left, below) , Great Danes, Portuguese Water Dogs, West Highland White Terriers (see photo on right, below), and Leonbergers are all predisposed to developing this disease.

Chain of events leading to severe hypoadrenocorticism in dogs

With primary hypoadrenocorticism (Addison's disease), the dog generally develops complete adrenocortical destruction with both cortisol and aldosterone deficiencies.

Aldosterone is the main mineralocorticoid hormone, and it affects the levels of potassium, sodium, and chloride in the blood. Low levels of aldosterone cause potassium to gradually build up in the blood and, in severe cases, cause the heart to slow down or beat irregularly. Some dogs have such a slow heart rate (50 beats per minute or lower) that they can become weak or go into shock.

Less commonly, dogs will develop secondary or "atypical” primary hypoadrenocorticism. This subgroup of dogs are only deficient in cortisol and appear to maintain a normal aldosterone level, at least early in the course of their disease. These dogs are more difficult to diagnose because their signs are milder and the serum potassium, sodium, and chloride values all remain normal.

Clinical features of hypoadrenocorticism in dogs

Historically, hypoadrenocorticism generally has a waxing and waning course and may be confused with other diseases because the clinical signs are not specific. The most common clinical signs and physical exam finding include the following:

- Depression or lethargy

- Weakness or collapse

- Anorexia (poor appetite)

- Weight loss

- Vomiting or diarrhea

- Excessive thirst and urination

- Hypothermia (low body temperature)

- Dehydration and shock

Signs of Addison’s disease include repeated episodes of vomiting and diarrhea, loss of appetite, dehydration, and gradual, but severe, weight loss. Because the clinical signs of Addison’s disease are vague and nonspecific, it can be difficult to diagnose in the earlier stages of disease. Therefore, severe consequences, such as shock and evidence of kidney failure, can develop suddenly in some dogs.

In my next post, I'll discuss how we can diagnose and treat hypoadrenocorticism, can will be fatal if not properly managed.

Źródło: nimalendocrine.blogspot.com

The growing concern surrounding the release of radiation from an earthquake and tsunami-stricken nuclear complex in Japan has raised fears of radiation exposure to populations in North America from the potential plume of radioactivity crossing the Pacific Ocean.

Because I use radioactive materials both to treat cats with hyperthyroidism (radioiodine; I-131) and to perform nuclear imaging procedures (ie, thyroid, bone, renal, liver scans— see my website for more information), many veterinarians have contacted me with questions and concerns.

Over the weekend, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, the American Thyroid Association, The Endocrine Society and the Society of Nuclear Medicine issued a joint statement written to help Americans understand their radiation-related health risks. I thought that many of you might find this helpful in understanding the situation and what you and your family should know.

RADIATION RISKS TO HEALTH:

A Joint Statement from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, the American Thyroid Association, The Endocrine Society and the Society of Nuclear Medicine March 18, 2011

Chevy Chase, MD (March 18, 2011)--The growing concern surrounding the release of radiation from an earthquake and tsunami-stricken nuclear complex in Japan has raised fears of radiation exposure to populations in North America from the potential plume of radioactivity crossing the Pacific Ocean. To help Americans understand their radiation-related health risks, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE), the American Thyroid Association (ATA), The Endocrine Society and the Society of Nuclear Medicine (SNM) issued a joint statement.

The statement suggests that the principal radiation source of concern, in regard to impact on health, is radioactive iodine including iodine-131.This presents a special risk to health because exposure of the thyroid to high levels may lead to development of thyroid nodules and thyroid cancer years later.

Radioactive iodine uptake to the thyroid can be blocked by taking potassium iodide (KI) pills. However the statement cautions KI should not be taken unless there is a clear risk of exposure to high levels of radioactive iodine. While some radiation may be detected in the United States as a result of the nuclear reactor accident in Japan, current estimates indicate radiation levels will not be harmful to the thyroid gland or general health. If radiation levels did warrant the use of KI, the statement recommends it should be taken as directed by physicians or public health authorities until the risk for significant exposure dissipates.

The statement discourages individuals needlessly purchasing or hoarding of KI in the United States. Since there is not a radiation emergency in the United States or its territories, the statement does not support the ingestion of KI prophylaxis at this time. KI can cause allergic reactions, skin rashes, salivary gland inflammation, hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism in a small percentage of people.

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, American Thyroid Association, The Endocrine Society and the Society of Nuclear Medicine will continue to monitor potential risks to health from this accident and will issue amended advisories as warranted.

Źródło: endocrinevet.blogspot.com

However, by following the protocol outlined below, you can easily dilute, aliquot and store Cortrosyn after reconstitution for up to 6 months. This makes each ACTH stimulation test much less expensive, because each vial of Cortrosyn can be used to perform as many as five ACTH stimulation tests.

Cortrosyn is supplied in vials each containing 0.25 mg (250 µg) of synthetic ACTH (cosyntropin) in powder form. Because the dose of Cortrosyn used to perform an ACTH stimulation test is only 5 µg/kg, small to medium sized dogs require only a fraction of the ACTH contained in each vial.

Cortrosyn is supplied in vials each containing 0.25 mg (250 µg) of synthetic ACTH (cosyntropin) in powder form. Because the dose of Cortrosyn used to perform an ACTH stimulation test is only 5 µg/kg, small to medium sized dogs require only a fraction of the ACTH contained in each vial.For more information on how to perform an ACTH stimulation test, see my post entitled, What's the best protocol for ACTH stimulation testing in dogs and cats?

How to aliquot and store each vial of Cortrosyn for subsequent use? It's simple — just follow the directions outlined here:

1. Reconstituted the Cortrosyn power by adding exactly 2.5-ml of sterile saline solution to the vial. With this dilution, the resulting concentration of the Cortrosyn solution in the vial would be 100 µg /ml.

2. Once Cortrosyn is reconstituted, aspirate 50-µg doses (0.5 ml) into 5 plastic syringes. Or, if smaller ACTH doses are desired, aspirate 25-µg doses (0.25 ml) into 10 syringes. (For more accurate dosing, I use insulin or tuberculin syringes).

DO NOT store reconstituted Cortrosyn in glass containers or vials. The reason that the Cortrosyn needs to be stored in plastic is that ACTH will stick to glass, thereby lowering the available amount of Cortrosyn that would be injected at time of testing.

3. The syringes containing the reconstituted, diluted Cortrosyn should be labeled with the product, dose in each syringe, and the date the Cortrosyn was reconstituted.

4. Freeze each of the syringes at -20oC. Avoid storing these syringes in a frost-free freezer, which must periodically warm up to de-frost. Repeated freezing and thawing cycles would compromise the integrity of the Cortrosyn.

When frozen properly, aliquots can be stored for up to 6 months without loss of efficacy.

5. Alternatively, the Cortrosyn solution can be stored refrigerated (4oC) where it has been shown to be bioactive and stable for at least 4 weeks.

Diluting the Cortrosyn and using a low-dose ACTH stimulation test protocol is very cost-effective. In this way, 1 vial of Cortrosyn can be used to test multiple patients without compromising the quality of the test results.

As an example, at the 5-µg/kg dose, 5 dogs weighing 10 kg (22 lbs) can be tested using a single vial, reducing the cost of the drug by 80%. By looking at the cost benefit, it is clear that the savings could be significant by using this testing protocol.

Źródło: endocrinevet.blogspot.com

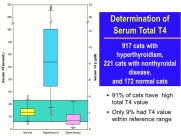

We are trying to concur on choice of the single best test to screen cats for hyperthyroidism. Is determination of total T4 still the gold standard for screening the majority of cats?

My Response:

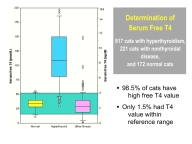

Use of a serum total T4 concentration is absolutely the best single screening test. But remember, the diagnosis of hyperthyroidism can never be based on a single total T4 alone. It has to be based on the presence of clinical features (eg. weight loss despite a good appetite) together with the presence of a thyroid nodule. If many clinical signs of hyperthyroid are present in a cat with a high total T4 but a thyroid nodule is not palpable, it's always a good idea to confirm the diagnosis by repeating the T4 and/or measuring a free T4 concentration.

Use of a serum total T4 concentration is absolutely the best single screening test. But remember, the diagnosis of hyperthyroidism can never be based on a single total T4 alone. It has to be based on the presence of clinical features (eg. weight loss despite a good appetite) together with the presence of a thyroid nodule. If many clinical signs of hyperthyroid are present in a cat with a high total T4 but a thyroid nodule is not palpable, it's always a good idea to confirm the diagnosis by repeating the T4 and/or measuring a free T4 concentration.

In some cats with mild hyperthyroidism, the total T4 can be high-normal or only borderline high. In these cats, a free T4 measurement is commonly used to help verify the diagnosis. The free T4 value should NEVER be run without a total T4; the specificity of the T4 is quite poor, and many cats without hyperthyroidism will have a high free T4  concentration. Therefore, the presence of a high free T4 with a normal T4 is not really diagnostic for hyperthyroidism unless the cat is showing clinical signs of the disease and has a palpable thyroid nodule.

concentration. Therefore, the presence of a high free T4 with a normal T4 is not really diagnostic for hyperthyroidism unless the cat is showing clinical signs of the disease and has a palpable thyroid nodule.

Again, without clinical features and physical exam findings consistent with hyperthyroidism, it's always best to wait and retest at 1-3 month intervals. Thyroid scintigraphy (see Figure on left) can also be a very helpful diagnostic aid in these cats. Cats with mild hyperthyroidism have an increased uptake of the radionuclide by their thyroid nodules. The percent uptake (or thyroid:salivary ratio) can be calculated and used as a sensitive diagnostic test for hyperthyroid cats.

Again, without clinical features and physical exam findings consistent with hyperthyroidism, it's always best to wait and retest at 1-3 month intervals. Thyroid scintigraphy (see Figure on left) can also be a very helpful diagnostic aid in these cats. Cats with mild hyperthyroidism have an increased uptake of the radionuclide by their thyroid nodules. The percent uptake (or thyroid:salivary ratio) can be calculated and used as a sensitive diagnostic test for hyperthyroid cats.

Sound difficult? Unfortunately, it is not always so easy to correctly diagnose hyperthyroidism in cats. But remember that treatment of hyperthyroidism is never an emergency, especially if the hyperthyroidism is very mild. If a 'borderline' cat does have hyperthyroidism, the thyroid nodule will grow and the total T4 will become high with time.

Źródło: endocrinevet.blogspot.com